The night I was God’s Co-pilot

The realization of what’s hoped for, and evidence of things not seen (Hebrews. 11:1-3)

WARNING: Adult content - language

By Danny “Hawkeye” Keuhlen

Some of these chapters (I only have this one chapter from you, Danny) have come easy, flowing from long thought about occurrences or events that I have come to grips with over time, but there are some events that need to be mulled over for years before their real significance is finally driven home. At some level, I think that happened today, Friday, 24 September, 2021. I was in Church at 07:00 at a Mass celebrated in honor of my Mom and Dad and I think I got a glimpse of the bigger picture.

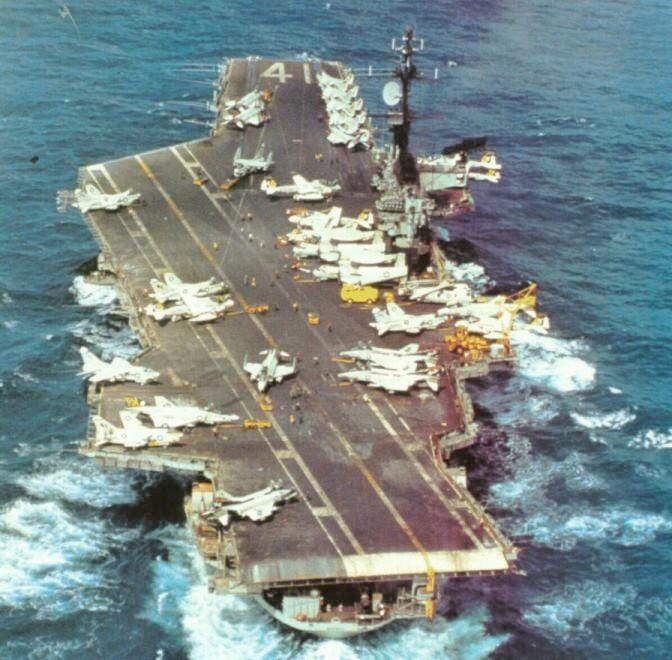

It was 1988 and I was flying E-2C Hawkeyes with the Liberty Bells of VAW-115 off the Aircraft Carrier USS Midway, CV 41, home ported out of Yokosuka, Japan—a Navy pilots dream match up. The Department of Defense used the USS Midway to cover every international contingency from the Persian Gulf to Hawaii. When you had to surge a Carrier and have a Naval presence somewhere around the globe, the Midway was always closest to the action. So, it was one of those tours with a lot of time at sea, and really tough on our families back in Japan.

I was a well-seasoned Navy Lieutenant Commander. A good pilot with 2500-ish flight hours. I was trusted to fly anytime, anywhere, day or night, good or bad weather and any Mission … and I could. I had great confidence in myself and my abilities.

No, I was not the Ace of the Base, but I could bring my Crew home in one piece, sleep 2 hours, and go back to war again.

The Midway was a throwback to World War II. Her keel was laid in 1943 but she didn’t commission until ’46. She missed the War. During the ensuing years, 1946-1986, her WW II design lived through some of the greatest Aircraft Carrier innovations the US Navy had ever seen. Innovations as simple as an angled flight deck, fiber optics instead of miles (yes, I said miles) of half inch copper wire that threaded its way through that ship.

Funny thing though, as these innovative technologies were added to the ship, to save money and time, the old stuff was never taken off. In the ensuing 40-plus years, she gained a lot of weight and sat so low in the water, she was limited in the Sea Ports she could visit due to her draft. Her gas mileage, which had never been that great, had gotten atrocious. Something had to be done.

How about we remove all that old stuff so she floats higher in the water?

So off to the Japanese Shipyard in Yokosuka she went and a yearlong complex overhaul was executed that saw hundreds of tons of old metal go over the side … and it worked. She sat higher in the water, and while she was in the yards, the Air Wing transitioned from F-4 Phantoms and A-7 Corsairs to all F-18 Hornets, E-2Bs transitioned to the E-2C. We killed alotta birds with one big stone during that yard period. It was good for the entire Battle Group.

Now, one of the few things I remember from a year of Naval Architecture Classes at the Boat School was about this little thing called “Metacentric Height.” Hold on a second. I’m gonna have to google this for you.

OK, it says, “The metacentric height is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the center of gravity of a ship and its metacenter. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stability against overturning. The metacentric height also influences the natural period of rolling of a hull. With very large metacentric heights being associated with shorter periods of roll which are uncomfortable for passengers ...” Anyway, you get the idea.

We raised the Metacentric Height on the ship, but between putting on new systems all over the ship—from 21” FAT CATS (Biggest Steam Catapult in the Navy at the time), to bringing onboard new Air Wing with the associated paraphernalia from aircraft weights, plus the number of Sailors that come aboard—and taking old stuff off the ship, no one figured out figured out how it would affect the Midway’s stability. Nobody looked at ship’s new handling characteristics. But the Midway’s draft decreased and everyone was happy.

Until she first went back to sea.

There were some real perturbations when Midway finally returned to water for a shakedown after a year in dry dock. During sea trials, the ship rocked and rolled like most Navy guys had never seen before.

The Battle Group Admiral bitched about the ship handling problems to the Naval Architects and Engineers who designed the Midway’s “overhaul” at the Navy’s Premier Ship Building School, the David Taylor Ship Research Facility in Annapolis. They came out to sea with us to inspect the problems themselves. On a clear day with only 6 foot swells, the ship’s movement was unequaled. In a bad way.

How bad? On one attempted landing on a clear beautiful day during sea trials, as the bow pitched down, I saw the ship’s two rear screws come out of the water. Wow. The Engineers said it was Ok. Of course, they didn’t have to land on it. We all thought they got their just desserts when one of them got cold-cocked by their huge VHS video camera as it slid off a shelf during one of the Midways rolls. Rumor was seven stiches to an Engineer’s head. I can neither confirm nor deny. Served them right, though.

Now I must ‘splain ships movements for a minute or two, so sit tight and concentrate. All ships at sea move in three axis, whether it’s a rowboat or this mighty behemoth at 85,000 tons. It just physics. Well, some other scholarly arenas might be involved, too.

The first movement is Pitch. Quite simply, the bow of the ship goes up, and so the stern goes down. No biggie, except the Midway’s bow was pitching 30 feet up in the air as the stern dropped 30 feet. Try landing on that 60-foot swinging son of a gun.

The second axis is Heave. This one’s a little tougher to explain. In big swells, the ship will stay somewhat level with the horizon and the bow and stern will rise and fall together plus or minus 30-40 feet up and down. Leastways the Midway did.

Then there’s that final axis. Think of that old geometry class you had. Your teacher would have called it the “Z” axis. Boy, did the Midway have a Z axis. Somewhere 450-ish feet forward of the stern of that ship, up by the Island superstructure, was the Midway’s “Z” axis and pivot point.

You’ve seen a figure eight before, right? For aviators, when you take that figure eight and lay it sideways, horizontal to the flight deck, we call that motion a Dutch Roll. Don’t ask me why, it’s just the way it’s always been called that. At the edge of a good Dutch Roll, that ship could move sideways and pivot 30-plus feet side-to-side.

Ladies and gentlemen, when the Midway was finally done with all the work in this extended Ship Yard period, she could move in all three of those axis’s simultaneously on a clear day. Not good. In bad weather, she was the worst I have ever seen in my 5,996 flight hours and 1,200 carrier-arrested landings. I have landed on every aircraft carrier in the Navy’s inventory, from CV-41 to the Truman CVN –75. I know my carriers and this set of axis properties is, frankly, untenable.

Some background now to help you understand my call to faith.

Taken right out of Wikipedia, some description is helpful. “The E-2C Hawkeye communication aircraft has a wingspan of 80 feet, 7 inches. The E-2C is a tactical airborne early warning (AEW) aircraft. It has served the US Navy around the world, acting as the electronic "eyes of the fleet." A distinguishing feature of the Hawkeye is its 24-foot (7.3 m) diameter rotating radar dome (rotodome) that is mounted above its fuselage and wings. The aircraft is operated by a crew of five, with the pilot and co-pilot on the flight deck and the combat information center officer, air control officer and radar operator stations located in the rear fuselage directly beneath the rotodome. Hawkeye provides all-weather airborne early warning and command and control capabilities for all aircraft-carrier battle groups.”

Remember that 80’ 7” wingspan measurement. The landing area on the carrier deck is only 400-ish feet long and 100 feet wide. Space is so critical on the flight deck that aircraft are parked on both sides of the landing area. That’s why there’s only 100’ left for landing. If you miss the center line of the runway by any more than nine feet either side, your wing will rip the nose off aircraft parked within inches of the landing area. Then you’ll crash, and chances are it won’t be a good day.

If in your mind you’re going “Jeeze, Tex, nine feet from wing to parked aircraft seems like a lot of room,” re-read the above paragraphs about the ships movement. You wanna know something else? Yeah, I’ll tell you something else. In bad weather on the steadiest carrier, you can’t see the ship you are trying to land on. On the reconstructed Midway in squal territory, that landing area can be wiggling every which way, all at the same time.

As I said, the Engineers said it was OK. There we were out to sea because they said it was going to be OK. It was not OK.

It was going to be a varsity night in the South China Sea. Thunderstorms, heavy rain, ceilings sometimes down to 100 feet, big swells, lots of wind, and no moon. The assigned skipper for the ship’s Hawkeye aircraft was going to take a brand-new nugget pilot who had just checked aboard the squadron a couple days prior out on his first night flight as co-pilot. It was this nugget’s chance to get his feet on the ground and see how the Air Wing operated at night.

At the last minute I got a call. The skipper couldn’t make his flight (go figure), and I was tapped for the pilot’s seat.

I hustled to the ready room and got everything ready for the brief. The mission wasn’t tough, it was a single cycle (1.5 hours) but the weather was dog shit. The really good news? It was prognosticated to get worse. We briefed every emergency contingency I could think of with my raw co-pilot. But truth be told, he was lost. Just like I had been eight years earlier. I was gonna have to keep an eye on him ...

As we manned up, the heavy rain started with real earnest. I hate pre-flighting an aircraft in the rain. There is no way to stay dry and the wind across the deck chills you to the bone. We were going into harm’s way, nonetheless, and I had to make sure this Bird was ready to fly.

We started engines, taxied to CAT 1 on the starboard side and waited. There was chatter on the radio about cancelling due to weather. That would not have pissed me off, but in the end we were a go and ended up being the weather recce for the entire launch. And launch them they did. Hornets were in the air.

They wanted us to check out the cloud tops at 22,000 feet. Yeah, got it. In the dark of night, we banged off the front end at 130 knots inside 160 feet, gear up, flaps up and the outside world disappeared as we went in the low, low clouds, sitting at 100 feet.

Passing through, finally, about 25,000 feet, we got above the clouds. But the lightning and thunder heads all around made it hard to really gauge what was out there. The rain never let up until we got on top. I told them we were into the goo and muck at 100 feet to flight level 250. The boss came up on the radio and said…” 99 School Boy (the Midway’s Call sign) ops for the night have been cancelled. Your signal is max conserve as we re-spot the flight deck for recovery.”

He had made the right choice. Just one E-2 in the air too late.

We descended to Angels 20 (20,000 feet) and went into holding. I was hanging on the blades (max conserve) We knew we’d be the last aircraft to return. The other aircraft recovery games had began down below.

The weather had deteriorated to worse than we had taken off in. The first 5 or 6 aircraft did not get back onboard. Most of them needed gas. The Hawking Tanker, an KA-6 Intruder, or airborne gas station, couldn’t find a clear spot in the clouds to refuel the Hornets in and it was getting dicey.

We just listened to the chaos and screams as Midway tried to recover all the aircraft aboard. The tanker and his chicks had to fly away from the carrier and do radar-controlled approaches to join up and get gas for the next attempt at landing. The decision was made to hold recovery as the flight deck prepared a second and third tanker for the 10-12 airborne aircraft. A second KA-6 Intruder configured to give gas launched and immediately started to rendezvous and give gas to Hornets before they flamed out.

On the radios all we heard were Power calls, then screams — Power, POWER, BURNER, BURNER, WAVEOFF — as aircraft after aircraft could not get aboard. The nearest land was 400 miles away. This was getting dangerous and I had taken off with less than a full bag of gas because, remember, we were supposed to be just a single cycle. I was starting to worry a little.

Now is as good a time as any to tell you about the Automatic Carrier Landing System (ACLS) installed on Carriers to help Aircraft get aboard in bad weather and at night.

First of all, it ain’t automatic. We have the system in the Hawkeye. It displays a set of crosshairs on the Gyro in the cockpit. They show you where you are left or right, high or low, on the perfect glidepath to a safe landing. In three dimensions, it’s like flying down a funnel. You set up a perfect 500 foot per minute rate of descent at three miles behind the boat at 1200 feet, keep the crosshairs centered. Then at 3/4’s of a mile, at night, you will see the meatball (visual landing system) centered and continue to a perfect visual landing.

The important point here is you still have to be able to see the meatball and landing area to land safely. With the weather, winds, ships Dutch Roll, pitching and heaving, those crosshairs move so fast that the “automatic“ system can’t keep up. Neither can you. That, and at the top of the funnel, you can be 100 feet left or right, 100 feet high or low, and the crosshairs will be centered. In other words, you’ll look good right up until you fly into the water.

We listened to this happening to our brethren below us as we waited for our turn. I had just reached Max trap on the Ball. That’s the heaviest that your aircraft can weigh without breaking the arresting gear. We were 25 miles from mother. I made the call to CATCC (Carrier Air Traffic Control Center) as an advisory. I had burned down 6,000 thousand pounds of gas just waiting. And the wait continued.

My co-pilot rolled his visor up and started asking a lot of questions. I did my best to assuage his concerns. Don’t worry, they’ll get aboard. But I could tell he was wasn’t buying it. I told him another ten minutes and it’ll be our turn. “I got this wired,” I assured him.

The next three Hornets and one A-6 Intruder waved off. They never saw the ship. Paddles, (the Landing Signals Officer on the flight responsible for the safe recovery of airborne aircraft) never saw the aircraft either. He’s standing on the stern of the ship in the rain, for goodness sake. That’s a really bad sign.

On our radios came the call. “99 School Boy (Midway’s collective call sign), max conserve, we are launching a third tanker. Stand by for vectors to get gas.”

Holy shit, I have never seen a third tanker launched. EVER. We were just under 3,500 lbs of gas. I called CATCC and told them. They said don’t worry, they had worked out a plan for the 5-6 aircraft still airborne. I said not good enough, we’re BINGO. (Bingo is emergency gas flight profile to get to land). We were heading to MCAF at Iwakuni, Japan to get on the beach before we flamed out. We needed an updated winds aloft and weather at the beach.

I started to climb on a bingo profile and then the radio transmission that will stay with me for the rest of my life time came over the tiny speakers in my helmet.

“99 School Boy, your signal is BINGO, Hook up, Gear Up. All aircraft are to join on the airborne tanker at Angels Three Zero in the clear and sip gas all the way to the beach. Take only enough to make it to Iwakuni. Your stear is . . . switch frequency . . . report safe on deck. Wind aloft are 75 knots on the nose.

OH SHIT. The winds had shifted to on the nose and increased 40 knots. I quickly punched my pubs with a sickly feeling. Oh Lord. We couldn’t make the beach. We would flame out at least 50 miles from terra firma. We had no choice. We were committed to landing back aboard Mother, or go swimming. And it was so bad down there, no one had made it aboard in over an hour. My gas showed 2800 lbs. I was 50 miles from mother.

On the radios I could hear the Boss telling the rain-drenched flight deck crew to wrap the landing area, the recovery was complete.

The Plane Guard Helo had to recover on one of our Destroyers. The Helo is airborne during recoveries to pull pilots outta the drink if we crash. The weather was so bad they couldn’t find the Carrier to land there either.

I immediately turned around, back towards Mother and decided my only choice was a downwind entry to land. I called CATCC and said, “CATCC…….E-2s CAN’T (I believe I said FUCKIN’) TANK.”

I was pissed at myself. I had let the Carrier Controllers get me in this situation. They had forgot about us, but it was my fault. We don’t have a refueling probe to inflight refuel. A fact that had escaped the chaos down below. After my transmission, the quiet on the radios was almost deafening. Not one transmission.

I closed the throttles and tried to trade every ounce of altitude to for gas. We were in trouble. The Captain of the ship came up on the radio and asked our fuel state. I said, “2,600 lbs Sir. Based on present consumption and distance, I estimate 1,200 lbs on the ball call. I think we only have enough gas for one try. if we miss, I’ll fly close aboard the ship and bail my crew out. I’ll … Well …” and I trailed off.

The Captain was quiet. He just said “Roger.” That means he understood. One landing attempt, and if we missed, people were gonna die. We were in deep shit.

I turned to my Nugget and said let’s do the pre-landing check list and get it out of the way. Nothing. I looked over at him and he was in one of those states where he was there … but nothing was getting through. Overloaded. Trust me. For three hours we had been listening to this chaos. It would have freaked out anyone. And I understood.

“CICO, Flight, (my senior of three Naval Flight Officers in the back of the aircraft) Pre-landing check List.” He did great. We went through it. I really tried to steady myself. I had lived through a lot over the years. A lot. Fires, single engine craft. I was still a wanted man in San Diego for dumping jet fuel all over La Jolla, California with a bird that was coming apart in the air. But this was different.

I didn’t have fear. I didn’t worry whether I was up to the task. Four guys were depending on me and this was going to be a no re-test night. We had one shot at it. Best guess was we had one pass before bailout. In this weather and these seas, no one would make it. It was sometime around 0100 in the morning.

We entered the really heavy rain at 15,000 feet. There was absolutely nothing to see…….Just the soft red glow of the instrument lights. At 3 miles on down wind, at 2,000 feet, still in a very slow descent to save gas, CATCC hooked us in to the final approach course. I had vertigo like I have never had in my life. I turned 20 degrees left, then CATCC said continue left turn to intercept Final Bearing. Final Bearing, that’s the runway/carrier’s heading. My body was screaming at me that we were in a right handed turn. I told my co-pilot I got vertigo and the leans really bad, so he should monitor my altitude and airspeed. “Do not let me get slow (air speed wise).” I got no response. Once again, I called to, “CICO Flight, you heard that, you got back up.” And he did.

CATCC said approaching three miles. ACLS Lock On, Say Needles. My crosshairs jumped from off, to slightly up and right. I said “Concur, slightly up and right.” And so it began. Gear down, “Landing check list” I called to my co-pilot. He was frozen. Nothing. Once more, “CICO Flight, Landing check list.”

Hook? Down, Gear? One, two, three down and locked, Flaps? 20, indicated, Max rudder?, 20, auto, indicated, Harness? Locked.

I said get ready boys, here we go. And then it was silent. I was alone. Me, this 46 thousand pound beast of a Hawkeye, and the steel or water that awaited me below. There was no second try.

There were no less than 50 personnel on the ship watching the approach on closed circuit TV. There was nothing to see. The cameras on the flight deck could only see a few feet around the flight deck because of the heavy rain. I am piloting an aircraft doing a 500 foot per minute descent at 130 knots, hurtling towards an unknown destiny three miles ahead. It dawns on me. I have never been here before, and I am alone. The feeling in the cockpit is the loneliest I have ever felt in my life. I begin to doubt. A little.

My needles swing wildly right, I gently put in some right wing down and a smidgen of power. They swing left now and drop lock. CATCC calls the drop lock and says take over visually. The rain is now falling so hard it drowns out the sounds of my engines. And my labored breathing. I call “CLARA.” That means I can’t see anything. Two miles.

Paddles (Landing Signal Officer out in the weather on the flight deck) comes up on the radio and takes over the approach. He knows the stakes. He is standing on the flight deck with me on voice. When he keys the mike to talk to me I can hear the rain in the background. His voice is soft. The kind of voice that could stop a charging bull. He knows if I crash, chances are I am taking him with me. He’s fully vested in this landing. He says, “Keep it coming Hawkeye.” and I do. It’s all that there is to do.

In all of this, I realize for the first time in my life, I am beyond my abilities as an aviator. It’s a strange feeling to have something like that just come over you. I’m…. Good, but this is a quantum leap beyond Good. This is beyond cheating death. Softly to myself I start doing the only thing a man in this situation can do. I started quietly praying to myself.

I realized that without His help, we weren’t gonna make it. And softly it began.

“Our Father, who art I heaven”

I don’t know how many times I said it as I flew down the pike from three miles out Time had lost all meaning. At three quarters of a mile behind the Midway and 200 feet above the water, CATCC said call the ball. That is where a pilot takes over visually and flies to touchdown. I said, “CLARA, fuel state 1.2”

Of the 10,000 pounds of gas I had taken off with, only 1,200 pounds remained. Everyone knew this was it. Looking straight ahead. Still descending into the blackness with nothing but a wall of water on the windscreen. Paddles said keep it coming. There was nothing else to do. There was nothing to see.

This was the most dangerous part of my pass. Below 200 feet above the water, the super structure of the Carrier is there. If I drifted right, I’d kill us all and a lot of folks on the ship. CATCC said half a mile. I was already illegal in my approach. I was at mandatory wave off if I couldn’t see the carrier, but it was moot. People would die.

“Hallowed be they name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done.”

The scream came over the radio into the silence of my helmet. “Tex, we got your lights. You’re high, work it down”

I still couldn’t see the ship. It was a black abyss. I pulled a little power.

“On earth as it is in heaven.”

“EEeaasy with it” Paddles said.

Time for more aerodynamics about landing on a Carrier. There is this thing called a “Burble.” As the winds rush over the Flight Deck bow to stern, from 20 to 40 knots, they rush off the angle deck and down towards the water. 60 feet below. It creates a massive area of disturbed air that pulls your wings in every direction and it creates a low pressure center just aft of the ship’s stern that sucks you down towards the water or the round down.

The round down is the blunt stern of the Carrier and it has killed many a Naval Radiator trying to get aboard.

Then it happened, the rush was like a drug entering my system. After the last three hours of total darkness, I was overcome by the deck rush of the landing area lights on the carrier as they appeared out of total black. Paddles screamed over the radio at the top of his lungs, “COME LEFT” He wasn’t asking. I did and I saw the Island. The ball was settling on the mirror big time. I was coming down like shit from a tall moose.

The Burble caught me under-powered coming back left. I went slow. I goosed the throttles to slow my descent as much as I dared, I prayed we clear the round down, God knows I hoped.

“On earth as it is in heaven.”

WE CLEARED THE ROUND DOWN. I slammed the throttles closed all the way to Flight Idle.

“Give us this day our daily bread.”

As I felt the airspeed bleed off, I reefed the nose back hard, set the Angle of Attack on my bird and waited for the landing gear to crash onto the flight deck with the prayer we would catch one of the three arresting wires on the deck. In the ensuing three seconds, I lived a life time. A friggin’ lifetime.

A carrier landing has been described as a controlled crash. This night, there was no control in my crash. Thank God that Grumman Iron Works builds Hawkeyes strong.

The main mounts slammed into the flight deck like a FREIGHT TRAIN INTO A SEMI. The sound was something awful. I jammed the power levers to full power. Those Allison T-56s engines were screaming to life. I stiff-armed them in less than a second My right arm was locked in place and the adrenalin was not going to let it move.

If I missed all three wires, I had to get this bird airborne and get my crew out.

“And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

The aircraft teetered onto the left main mount and then the right due to my last minute line up correction to not hit the Carrier’s island and kill us all. We waited and slammed the deck so hard we hook-skipped number one wire. The tail hook literally bounced off the steel flight deck and over the one wire. We waited.

”And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.”

We hooked-skipped number two. Shit. We going over the side. And then it happened…..

There is a feeling that every carrier aviator can tell you about. It’s the feel as the Tail hook engages a wire.

I don’t really have the words here. There is an audible noise the tail hook makes as it drags 70 feet behind you across the solid steel flight deck, snags a wire and snaps from full down to the full up position and drags the wire out. You can actually feel it in your butt. Or, is it the deceleration from 130 knots to nothing in 250 to 300 feet? Or, the visuals outside as the flight deck rushes by in reverse as your mighty beast slows and comes to a halt, 10 feet from going over the side and into the water. I don’t know what to tell you.

We had caught the Number three wire. Our last hope from death.

Amen.

My right arm on the throttles was locked in place. I couldn’t move it. A yellow shirt flight deck director ran in front of the aircraft and gave me the throttle back signal. I still had the wire engaged in the hook and the flight deck couldn’t retract it until I throttled back. But my arm wouldn’t move. I was spent. Every sense I had, every part of my body was overwhelmed. I was frozen.

The Air Boss came up on the radios and said, “Liberty Bell, we got you. You’re safe. Throttle back and follow your director.”

I guess that snapped me back out of it. Wherever I had been.I throttled back. We spit the wire. I raised the hook, and the yellow shirt wanted to taxi me to parking on the flight deck. I called the Boss and said “Chain and chock me here, Boss. You can tow me when the rain stops. I’m done for the night.”

There was a pregnant pause on the radios, no one, NO ONE, tells the Boss what to do on his flight deck with his flight deck crew. But tonight he just said, “OK Hawkeye.” He was an aviator too. He understood what had just happened.

I put on the parking brake, reached over and shut down both motors. It was a good 20 minutes before my legs would support me and I could get out of the aircraft.It was still raining … hard.

There were many accolades that night, but the adrenaline racing through my veins made it all pass in foggy slow motion. For the first time in my life, as I stared in the mirror in my tiny coffin-sized bunk room, alone at 04:30, still wired and unable to sleep, I had to ask myself what had really happened. In that three miles … in that two minutes … I had clearly exceeded the talents God had given me. I had been in many tight spots. More than once violated physics, but always managed to bring it back. Jeeze, I’m the only guy to ever do an inverted spin in an E-2 and live.

So what had really happened?

Socrates said something like the unexamined life was not worth living. Looking straight ahead, I asked the mirror man who was really flying? Who? And why?

For a long time I didn’t know the answer. Or better yet, I didn’t want to face that answer. But today, in Church, at Mass, praying for my Mom and Dad who instilled these tenants of Faith in me, I think I do now. For reasons that only God in his magisterium knows, we were saved for some other day. Some other thing that we will probably not learn about until the next life.

My crew that night, well, we never talked about what happened. My co-pilot has had a long and well deserved career. I don’t remember the LSO who was on the platform that night, but Paddles saved us as sure as the day is long. So many people came together for a simple landing, in the middle of nowhere, 400 miles from land.

God gives us all talents. He says don’t bury them. Invest what I have given you for the betterment of all. In the end you’ll understand. One day when you come home.

This is very personal for me. I have rarely ever spoken about this night and never written about it, but that night my Faith, which hadn’t grown cold but was not as strong as my younger days was renewed. Maybe my place in this drama was not pilot, but storyteller for you.

I believe, Lord. Help me in my unbelief. And I have finally unburdened myself of this chapter in my life. The night I was God’s co-pilot.

© 2025 John Francis Pearring

Privacy ∙ Terms ∙ Collection notice

Substack is the home for great culture